The euro is the commonly accepted currency for 17 of the 27 member states of the European Union; these countries combine to create the eurozone. To truly understand the euro as a currency is to understand the history of the eurozone.

The Positives

The eurozone is a negotiated partnership between participating countries of the European Union (EU), to share the economic and political benefits typically only associated with larger countries. The synergistic expectations and economies of scale projections from the agreements made between these countries were expected to have a positive, long-lasting impact for all member nations. The European Union itself began developing just after WWII as a way to foster a peaceful and economically stable Europe.

The European Union offered: peaceful coexistence; the reduction of border restrictions, allowing for free travel; combined strength and influence on a global scale; increased prosperity (though not equally among countries); a multilateral promotion of human rights; the promotion of new ideas to reduce global warming, and most notably, the use of a single European currency - the euro.

The euro was designed to ease the process of providing services, transporting goods and moving capital between euro-using nations. The goals of the euro were well thought-out with the highest of hopes, but the results have been mixed.

The initial rules regarding the requirements for a country to migrate from its home currency to the euro were well-defined and meant to exclude weaker countries, while creating a relatively stable relationship between countries meeting similar criteria. The official rules were spelled out in the Maastricht Treaty of 1992 that defined how members of the European Union could move into the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) and ultimately, the euro.

The Maastricht criteria, as they were coined, consisted of: inflation, a maximum of 1.5% above the average of all members; government debt and deficit restrictions; exchange rate rules and long-term interest rate level restrictions. Once all of the kinks were ironed out, the euro came to life in 2002 (although dates vary for a few countries) and is now the second-most traded currency behind the U.S. dollar, with which it was pegged at par at issuance.

Problems with the Countries Using the Euro

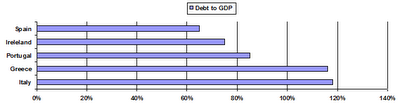

Part of the problem associated with the euro is the divergence from the original criteria for participation in the EMU. The most problematic issue has been debt. The original restrictions were set at a maximum of 60% of government debt as a ratio to gross domestic product (GDP); some countries (with the PIIGS as the worst offenders) have debt-to-GDP ratios reaching over 100% of GDP (see graph).

Source: European Commission Q2 2011

The irony is that the agreement between the EU countries and ultimately the EMU was to increase borrowing limits with the expectations that the leverage could be used to advance each country's specific needs. Debt always has a double-edged sword as its powers can be magical when used correctly. Italy, for example, was able to use its increased borrowing powers to increase both its national standard of living and its nationwide education level to become competitive in the global economy. However, this success has come at a serious long-term financial cost and may ultimately lead to Italy being required to restructure, redesign or possibly default on its debt.

Greece has a debt-to-GDP ratio similar to Italy and found its way into the doldrums by supporting its massive sovereign infrastructure through employing more than half of the population and taxing them at minimal levels.

Spain has not accumulated as much debt as Greece since it began using the euro, and has experienced rapid internal growth with its newfound access to capital. They chose yet another path; primarily in the form of private sector construction that had lain stagnant since the end of WWII. In Spain's case, instead of running an excessive debt-to-GDP ratio, its trade deficit ballooned since the construction pace was not sustainable and not a cross-border traded good. Spain faces the challenge of redirecting its efforts to a more balanced economy, including higher levels of exports that may take years to fine tune the balance.

Whatever the road traveled to, these debt levels have cast a shadow on the euro. The grand plan to provide some sort of simplicity and reversion towards the mean for the criteria on which the EMU and the euro were based on, seems to have actually had a reverse effect. In hindsight, one might easily wonder why and how so many different countries with so many different languages, customs and histories could ever share a common currency and be expected to progress and age at the same rate.

The Euro's Path

The euro was pegged in parity (1:1) with the U.S. dollar during its onset. At this point, all previous home currencies were abolished and the new euro was established and allowed to float with other currencies. While there were years of volatility, the immediate move was a divergence in price in favor of the euro, as the U.S. dollar weakened annually, peaking during the economic banking crisis at around 1.6:1. Since the 2008 crisis, volatility has continued but the general trend has been a stronger euro, even as debt and deficit levels have increased.

The Bottom Line

While the evolution of the EU seems to have been beneficial for the most part, the debate will rage on as to whether the assumption of a single currency for only part of the EU was the best idea. The ability for its participants to borrow more money at lower rates has helped each country in its own way to develop and grow, but at a great price.

The value of the euro has been high since its inception, and during the banking crisis it was considered a safe haven while investors fled from the U.S. dollar. Many countries have learned over the years that a strong currency is not always as good as it sounds. It can make your exportable goods more expensive, creating trade imbalances, which does not combine well with ever-expanding debt levels. Only time will tell the fate of the euro. While it is still one of the most attractive-looking currencies in the world, the grand design may be fading after over a decade of life.

Try trading the Euro by Trust Capital Demo account.

No comments:

Post a Comment